Collecting ejecta from an alien volcano.

During a hyperspeed fly-through of an active plume six miles above Io’s surface, a spacecraft would collect half a gram of dust and return the sample to Earth for study in the lab. Ogliore and his colleagues are determining the best materials to be used in the collector by simulating the whole process, from hyperspeed collection to lab analysis.

First, an analog to Io’s volcanic plume particles needed to be created. Mike Krawczynski, associate professor of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, supplied a sample of glass from a Hawaiian volcano which was then ground to the appropriate size by undergraduate physics student Saanya Manoj and research engineer Hélène Craigg. Ogliore then took the powder and several candidate collector materials to the University of Kent in England to work with colleagues Penny Wozniakiewicz, Mark Burchell, and Luke Alesbrook on their two-stage light-gas gun.

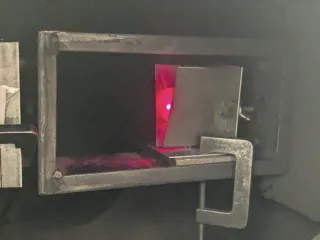

“We loaded the powdered glass into a projectile and shot it into pure gold, indium, silicon, germanium, and aerogel,” said Ogliore. The gun uses a shotgun cartridge and hydrogen gas to accelerate the projectile to several kilometers per second before it smashes into the target materials.

“Based on the speed and the material properties of the projectile and target, the projectile can bounce off, stick, melt, or vaporize. We don’t want it to bounce or vaporize, otherwise what we measure in the returned sample would not be the same as Io.” Measurements of both the pristine powder and the powder shot into various possible collector materials will reveal any differences. The best collector material is the one that yields the smallest difference.

“I’m kind of rooting for the pure gold, it’s very beautiful,” Ogliore said. He will work with Kun Wang, associate professor of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, in the coming weeks to analyze the samples.

Even a tiny pinch of Io in the lab will allow cosmochemists to see back to the formation of the Galilean moons from Jupiter's primordial circumplanetary disk, and Io's early evolution. Cosmochemical modeling of Io is led by Zoltán Váci, a postdoctoral research associate, who also developed techniques to measure the analog sample. Váci's models build upon pioneering work on magma transport in Io's interior by WashU's Thomas C. O'Reilly and Geoffrey Davies in the early 1980s.

Ogliore, Krawczynski, Wang, Craigg and Váci are all affiliated with the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences which funded this preliminary study. If selected as part of NASA's New Frontiers Program, the Io sample return mission could launch in the early 2030s.

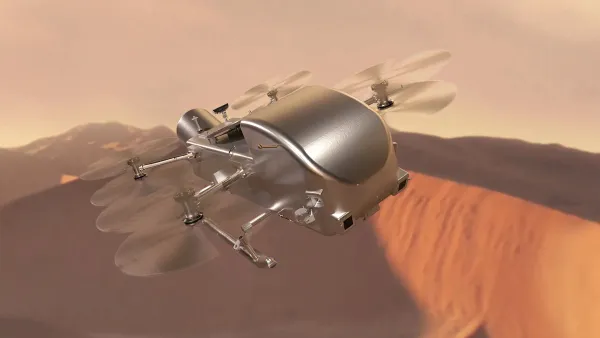

Animation of the Mission Concept

Header image: This color image, acquired during Galileo's ninth orbit around Jupiter, shows a volcanic plume on Io. It was captured on the bright limb or edge of the moon, erupting over a caldera named Pillan Patera. The plume seen by Galileo is 140 kilometers (86 miles) high, and was also detected by the Hubble Space Telescope. (Credit: NASA/JPL)